Engineering fundamentals I learned from Lego League

My thoughts on how years of Lego robotics competition shaped my career as a Software Engineer. Reading time - 7 minutes

December 15, 2019

Like many young children, I spent the majority of my youth obsessed with Lego. It started with mismatched hand-me-downs from cousins and neighbors and grew until an entire corner of the family room was dedicated to the Lego pile.

LEGO Mindstorms

In 1998 in collaboration with MIT, Lego released a new Lego-based robotics set called the Robotics Invention Kit, or Lego Mindstorms. It included a microcontroller called the RCX which included three inputs for sensors, and three 9v outputs for motors. There were touch sensors, light sensors, rotation sensors (which could monitor how many turns a Lego axle piece made), and more. Development occurred in a GUI editor on a PC, and the RCX could be programmed via a built-in infrared receiver. The entire system was ingenious. It was possible now to build the Lego robots I had always dreamed of - and animate them!

FIRST Lego League

In 1999, FIRST Robotics introduced the FIRST Lego League (FLL) competition. The competition format consists of a formal challenge based on real-world problems like space exploration, climate change, city planning, and natural disaster relief. Teams were responsible for two core deliverables: The first was a research project centered around solving the real-world problem issued in the challenge statement. The second was designing, building, and programming a Lego Mindstorms based robot that would navigate a competition table and solve various missions to earn points. The rules were simple - Robots must be autonomous. Once the team pressed the run button on the RCX, they had to let the robot go. Then they had two and a half minutes to collect as many points as possible.

In Orbit (2019 challenge) table.

In Orbit (2019 challenge) table.

The competition table included numerous creative challenges that fell into a few categories. Retrieval or delivery missions, where the robot would need to traverse the map, grab (or drop) an object, and bring it back to the home base. Manipulation missions, where the robot would trigger a spring-loaded launcher, flip a switch, or deploy some kind of simulated rover. Cross-table missions had teams reaching an objective straddling either team’s competition table. Sometimes it was a race where only one team could get points, other times it was cooperative, where both teams gain points if they each complete the mission, but no points for only one side completes it.

You can get an idea of the types of missions from this impressive practice run from a team at the 2018 competition. Note the use of a modular platform, mission-specific attachments, and mission prioritization. Fascinating stuff!

At the time I was an avid reader of Lego magazine, and frequently brought issues to school to share with friends. In 1999, First Lego League’s inaugural season commenced with “First Contact”. After the national tournament ended, Lego Magazine published an expose. A friend and I became obsessed and eventually convinced a few parents (and their employers) to sponsor a team at our school.

We were hooked.

I ended up competing for four years of challenges; specifically Volcanic Panic, Arctic Impact, City Sights, and Mission Mars. Later on, in high school, I returned to help coach for three more years. The program taught me so much, including how to work as a team, how to cope with failure, and how to think about complicated problems. Looking back, I also learned several fundamental lessons about software design that I’ve carried with me into my career.

Lessons

The original Lego Mindstorms kit was revolutionary at the time, but at the end of the day, it was still based on Lego Technic. The tolerances of components such as motors, sensors, and the RCX were a challenge in and of itself. Compared to a simple stepper motor and machined parts, Lego technic components were laughably imprecise. This lead to a whole host of engineering problems that we solved with both software and hardware.

The power of good (hardware or software) abstractions

Our original robot design circa 2000 was exactly what you might build at home. A small platform with two drag wheels and two drive wheels, with one motor connecting each drive wheel, and then some kind of arm on top.

In our naivety, we’d simply point the robot at a dead-simple out-and-back mission by setting both wheels to 100% for, say, 20 seconds. What happened next was infuriating.

Sometimes the robot would reach the destination. Sometimes it would drift off left, sometimes it would drift off right.

Initially, we realized that the RCX power delivery would degrade with battery life. To solve this, we replaced our time-based approach with a rotation sensor on one wheel. But that only uncovered more problems.

We learned that even if two motors were identical, there was enough slop in the gear system which delivered power to the wheels that we’d never be able to precisely navigate the competition table. Even with the rotation sensor (somewhat) accurately determining how far we’d gone - we could only measure on one side!

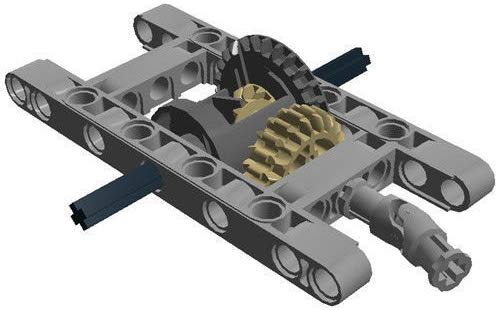

With some help from our coaches, we discovered that we’d need a differential gearbox!  Differential gear This allowed one drive motor to drive both wheels forwards or backward, and the second drive motor to turn the robot left or right.

Differential gear This allowed one drive motor to drive both wheels forwards or backward, and the second drive motor to turn the robot left or right.

This was my earliest lesson in how to solve a complex problem using abstraction - but of course, this solution also brought new problems.

Composability and software reuse

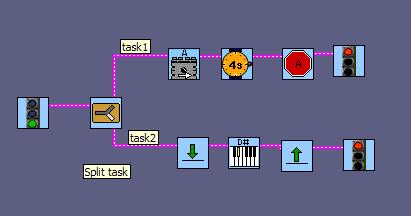

Naturally, the differential gearbox made programming more complicated - until we discovered subroutines! We could define user-created blocks that we’d call forwards, backward, left, and right.

As with all software projects, at some point the requirements changed and we needed to adapt. During 2001’s Arctic Impact challenge, we realized we needed to redesign our arm to rescue the scientists from lego polar bears, and also retrieve ice core samples. This eventually led us to switch from wide, drag-race style wheels, to the larger diameter, skinnier wheels.

Of course, this now meant that every single program needed to change! Suddenly one axle rotation resulted in much more distance traveled. We were so frustrated with how much time it took to edit each value for every mission - until we realized that we could encapsulate these values into higher-order programs like follow-right-line, 90-degree-turn, and back-to-base. The next time major platform changes occurred, we were able to respond to that change much more quickly.

After discovering both the differential drive system and the subroutine capabilities of our development kit, we were able to naturally build software without thinking about the underlying complexities like gear-slop, motor drift, or the complications of our differential. This abstraction allowed us to keep the same drive platform and subroutines for many years.

During my time in Lego League, our robot platform was pretty tightly coupled to the modular arm system we had designed. We’d just swap out one or two parts for different missions. Modern FLL strategy prescribes a wheeled platform, which entire skeletons are placed over for specific missions. Check out this incredible 2018 practice run by a team from Malaysia.

Managing environmental complexity

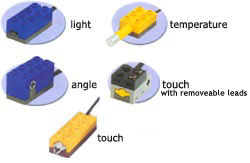

The original RCX kit had several sensors, but the FLL competition limited teams to three types - light, touch, and rotation sensors.

The competition map included several strips of electrical tape that acted as paths that a robot could follow using the light sensor. My initial algorithm was quite rudimentary. To follow the right side of a line: turn left if the robot saw the white competition mat, and turn left if it saw the black electrical tape. The robot would sort of wiggle down the line until a prescribed number of rotations were met. The sensor data wasn’t raw lumens, but rather a percentage of light-to-dark values.

Normally we’d have Lego League practice after school, under bright fluorescent lights. It wasn’t until our first all-night programming blitz (where suddenly nothing worked), that we learned just how much ambient light would impact the light sensors readings.

At the time, the actual competition was conducted in a dark gymnasium with one overhead fluorescent light over each table. Because each environment was so different, we determined we’d need to build a subroutine that would set a light and dark percentage threshold at the beginning of our robot run. Then instead of simply hardcoding light sensor values, we could get a much more accurate reading for our line following algorithms to use.

We also learned that sometimes it’s easier and more reliable to just build a mechanism that could straddle the 2x4 piece of wood that comprised the competition table border and force the robot down one line. Not everything needs to be done in software.

Lessons learned: Just because it worked on my machine, doesn’t mean it’ll work in the real world. It’s better to be adaptable than it is to toil over perfectly replicating your production environment.

Engineering reliability in a complex system

Although a reliable drive system was paramount for navigating the competition field, we also needed to build systems that could interact with the missions. Our early attempts were simple arms connected to a motor either directly, or with a series of circular gears.

This posed several challenges - we could only use one rotation sensor (and it was needed for the drivetrain), so we once again resorted to time-based motor control. This sort of worked, except that our drive system allowed for backdrive - where the force of the load on the end of the arm could turn the motor and drop the cargo, or wreck our precious timing.

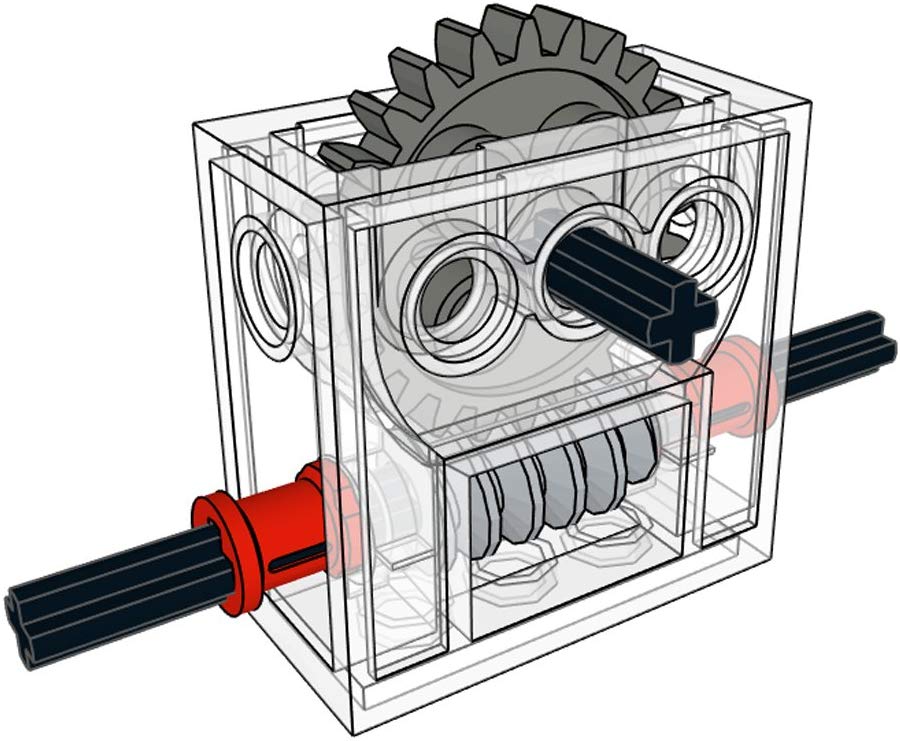

We needed an idempotent solution to our backdrive conundrum. This was solved using a worm gear, which is effectively a one-way drive system. The worm gear would turn a circular gear - but the circular gear could not turn the worm gear. This prevented whatever we were lifting from pulling the arm down to the table.

Worm Gear

Worm Gear

That left us with solving our reliability problem. We had already learned our lesson about using timers from our drivetrain woes. Since we didn’t have another precise rotation sensor at our disposal, we fashioned one from a touch sensor that would actuate as the arm passed over.

Now we could write another subroutine called arm-up or arm-down, and be confident that no matter how much weight was on the end of our arm, we wouldn’t stop raising or lowering the arm until it was in the desired position.

Wrapping up

One of the great things about FLL is that we were having too much fun solving problems and building robots that we didn’t realize we had effectively signed up for extracurricular schooling. That said, fundamentals like abstraction, composition, managing complexity, and reliability must be learned some way. I’m certainly grateful for the opportunity to participate in the early days of FLL, and I’m hoping it’ll continue to exist for a long time.