You shouldn't use Lambda layers

AWS Lambda layers can help in certain, narrow use cases. But they don't help reduce overall function size, they don't improve cold starts, and they leave you vulnerable to a particularly nasty bug.

November 8, 2023

Why you shouldn’t use Lambda layers

Lambda layers are a special packaging mechanism provided by AWS Lambda to manage dependencies for zip-based Lambda functions. Layers themselves are nothing more than a sparkling zip file, but they have a few interesting properties which prove useful in some cases. Unfortunately Lambda layers are also difficult to work with as a developer, tricky to deploy safely, and typically don’t offer benefits over native package managers. These downsides frequently outweigh the upsides, and we’ll examine both in detail.

By the end of this post, you’ll understand the pitfalls of general Lambda layer use as well as the niche cases where layers may make sense.

Busting Lambda layer Myths

When I ask developers why they are using Lambda layers I often learn the underlying reasons are misguided. It’s not their fault entirely, the documentation makes some imprecise claims which may perpetuate these myths.

Lambda layers do not circumvent the 250mb size limit

I frequently hear folks say they are leveraging Lambda layers to “raise the 250mb limit placed on zip-based Lambda functions”. That’s simply not true. The size of the unzipped function and all attached layers must be less than 250mb.

This misunderstanding springs from the very first point in the documentation which states that Lambda layers “reduce the size of your deployment packages”. While technically it is true that the specific function code you deploy can be reduced with layers, the overall size of the function when it runs in Lambda does not change.

This leads me to my next point.

Lambda layers do not improve or reduce cold start initialization duration

Developers often mistake that a “reduced deployment package” size will reduce cold start latency. This is also untrue, as we already know that the code you load is the single largest contributor to cold start latency. Whether or not these bytes come from a layer or simply the function zip itself is irrelevant to the resulting initialization duration.

Development pain with Layers

One of the biggest challenges for developers leveraging Lambda layers is that they appear magically when a handler executes. While that feat is impressive technically, it poses an issue for developers as text editors and IDEs expect dependencies to be locally available, as do bundlers, test runners, and lint tools. If you run your function code locally or use an emulator, only a subset of those tools cooperate with layers. Although solving these issues is possible, external dependencies provided by Lambda layers require special consideration and handling for limited benefit.

Often, the process of building and deploying Layers separately is enough to avoid them, but there are other reasons to avoid Lambda layers.

Cross-architecture woes

We’re writing software for a world which is increasingly powered by ARM chips. It may be your shiny new M3 laptop, or Amazon’s own (admittedly excellent) Graviton processor. Your Lambda functions are likely running on x86 or a combination of ARM and x86 processors today.

Lambda layers do support metadata attributes called “supported runtimes” and “supported architectures”, but these are merely labels. They don’t prevent or enforce any runtime or deployment time compatibility. Imagine your surprise when you attach a binary compiled for x86 to your arm-based Lambda function and receive exec format errors!

I demonstrated this failure live

Deployment difficulties

Lambda layers do not support semantic versioning. Instead, they are immutable and versioned incrementally. While this does help prevent unintentional upgrading, incremental versioning offers no clues as to backwards compatibility or changes in the updated layer package. Additionally, Lambda layers are completely runtime agnostic and offer no manifest, lockfile, or packaging hints. Layers don’t provide a package.json, pyproject.toml, or gemspec file to ensure adequate dependency resolution. Instead it’s incumbant on the authors to only package compatible code.

One of the main selling points of Lambda layers is that they can share common dependencies between many functions, which is great if every function requires exactly the same compatible version of a dependency. But what happens when you want to upgrade a major version?

You’ll need to release a new version of the layer with the new major version, ensure that no developer accidentally applies the incrementally-adjusted layer (remember – no semantic versioning, manifest files, or lockfiles!), and then simultaneously upgrade the Lambda function code and layer at the same time.

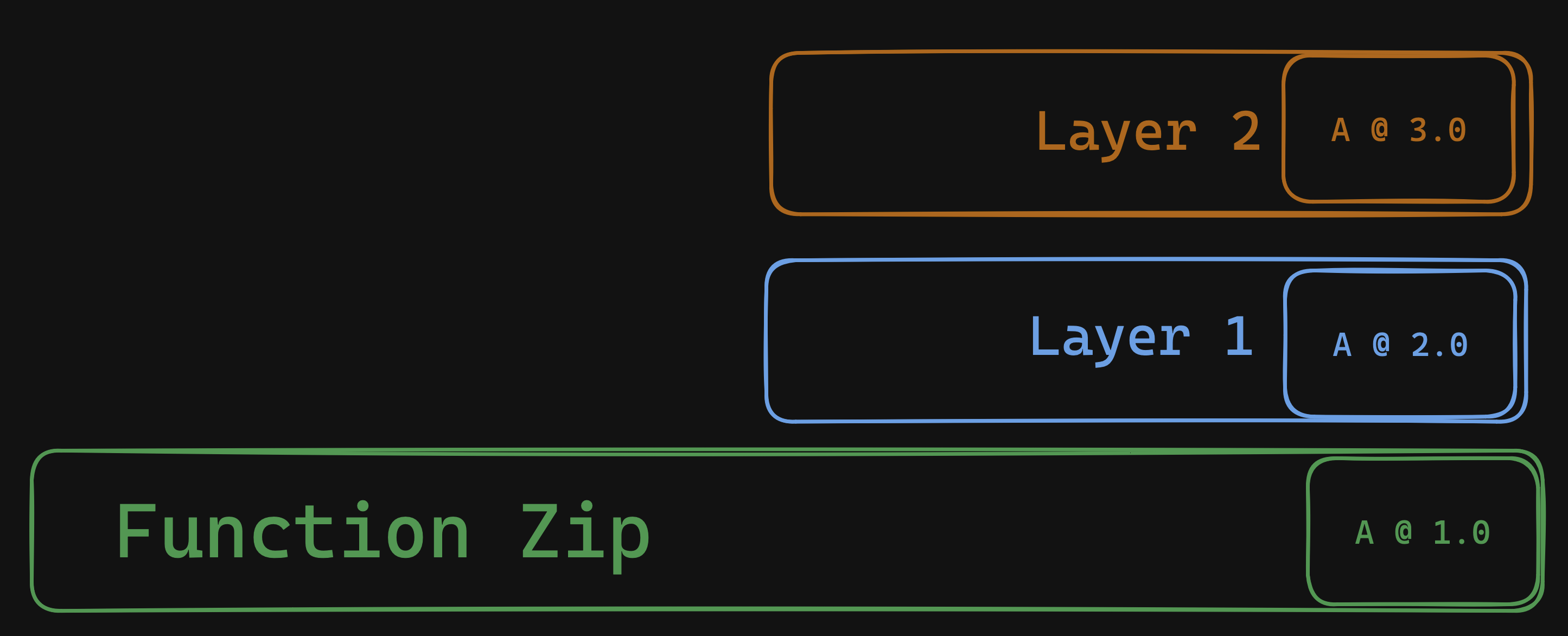

But even that doesn’t work out automatically, as I’ve already documented. Deploying a function + layer results in two separate, asynchronous API calls. updateFunction updates the function code while updateFunctionConfiguration updates the configured layers, and both of these are separate control plane operations which can happen in parallel. This means that invoking $LATEST will fail until both calls complete. To avoid this you’ll need to create a new function version, apply the new layer, and then update your integration (eg: ApiGateway) to point to the new alias, after both steps are complete.

Now semantic versioning is not perfect, and flexible specification (eg: ~ or ^ for relative versions) means that the combination of bits executing your Lambda function may run together for the very first time in a staging or production environment. This has caused enough issues that package managers have solutions like npm shrinkwrap, but this can be even worse with Lambda layers.

And that’s the gist of my point – this is what your package manager should be doing.

Dependency collisions

Lambda layers can cause a particular nasty bug and it stems from how Lambda creates a filesystem from your deployment artifacts. If you’ve followed this blog, you know that zip archives themselves can already create interesting edge cases when unpacking a zip file onto a file system, and Lambda is not immune to that. When a Lambda function sandbox is created, the main function package is copied into the sandbox and then each layer is copied in order into the same filesystem directory. This means that layers containing files with the same path and filename are squashed.

Although Lambda handler code is copied into a different directory than layer code, the runtime will decide where to look first for dependencies. This is typically handled by the order of directories listed in the PATH environment variable, or the runtime-specific variant like NODE_PATH, Ruby’s GEM_PATH, or Java’s CLASS_PATH as documented here.

Consider a Lambda function and two layers which all depend on different versions of the same library. Layers don’t provide lockfiles or content metadata, so as a developer you may not be aware of this dependency conflict at build time or deployment time.

At runtime, the layer code and function code are copied to their respective directories, but when the handler begins processing a request; it crashes with a syntax error! But your code ran fine locally?! What happened?

The code and dependencies in the Lambda layer expect to have access to version 2 of library ABC, but the runtime has already loaded version 1 of library ABC from the function zip file!

If this seems farfetched, it can happen to you – because it happened to me.

What Lambda layers can do for you

Lambda layers can improve function deployment speeds (but so can your CI pipeline)

Consider two Lambda functions of identical dependencies, one with using layers (A), and one without (B). It’s true that you can expect relatively shorter deployments for A, if you aren’t also modifying and deploying the associated layer(s). However the vast majority of CI/CD pipelines support dependency caching, so most users have clear paths towards fast deployments regardless of their use of layers. Yes, your CloudFormation deployment will be a bit longer but ultimately there is not a distinct advantage here.

Lambda layers can share code across functions

Within the same region, one layer can be used across different Lambda functions. This admittedly can be super useful to share libraries for authentication or other cross-functional dependencies. This is especially useful if you (like me) need to share layers for other users, even publicly.

I don’t really agree with the other two points in the documentation. Layers may “separate core function logic from dependencies”, but only as much as putting that dependency in another file and importing it. Your runtime does this already so this point falls a bit flat.

Finally, I don’t think it’s best to edit your production Lambda function code live in the console editor, and I especially don’t think you should modify your software development process to support this. (Cloud9 IDE is a good product, just don’t use the version in the Lambda console.)

Where you should use Lambda layers

Lambda layers aren’t all bad, they’re a tool with some sharp edges (which AWS should fix!). There are a couple exceptions which you can and should use Lambda layers.

- Shared binaries

If you have a commonly used binary like ffmpeg or sharp, it may be easier to compile those projects once and deploy them as a layer. It’s handy to share them across functions, and this specific layer will rarely need to be rebuilt and updated. Layers are best with established binaries containing solid API contracts, so you won’t need to deal with the deployment difficulties I listed earlier pertaining to major version upgrades.

- Custom runtimes

The immensely popular Bref PHP runtime is available as a Layer. Bref is available precompiled for both arm and x86, so it can make sense to use as a layer. The same is true for the Bun javascript runtime. That being said - container images have become far more performant recently and are worth reconsidering, but that’s a subject for another post.

- Lambda Extensions

Extensions are a special type of Layer but have access to extra lifecycle events, async work, and post processing which regular Lambda handlers cannot access. Extensions can perform work asynchronously from the main handler function, and can execute code after the handler has returned a result to the caller. This makes Lambda Extensions a worthwhile exception to the above risks, especially if they are also pre-compiled, statically linked binary executables which won’t suffer from dependency collisions.

Wrapping up

In specific cases it can be worthwhile to use Lambda layers. Specifically for Lambda extensions, or heavy compiled binaries. However Lambda layers should not replace the runtime-specific packaging and ecosystem you already have. Layers don’t offer semantic versioning, make breaking changes difficult to synchronize, cause headaches during development, and leave your software susceptible to dependency collisions.

If or when AWS offered semantic versioning, support for layer lockfiles, and integration with native package managers, I’ll happily reconsider these thoughts.

Use your package manager wherever you can, it’s a more capable tool and already solves these issues for you.

If you like this type of content please subscribe to my blog or reach out on twitter with any questions. You can also ask me questions directly if I’m streaming on Twitch or YouTube.